The Ocean’s Menagerie by Drew Harvell is more than a book about marine life — it is a journey into how evolution engineered some of the most advanced biological technologies on Earth. Each chapter introduces a different group of marine invertebrates and reveals a unique ability they possess — from coral reefs that build limestone skyscrapers, to sea slugs that steal stinging cells, to octopuses that shapeshift in milliseconds.

As someone interested in nature-inspired design and engineering, I was fascinated by how many of these abilities mirror — and often surpass — human technologies. Sponges invented fluid pumps long before humans built pipes. Corals discovered additive manufacturing and fiber-optic lighting. Sea slugs mastered chemical theft. Giant clams engineered living solar panels. Octopuses developed neural-controlled camouflage. Jellyfish invented molecular light. Sea stars created programmable stiffness materials.

This article summarizes each chapter of the book — not just to describe these organisms — but to highlight how their biology works, the science behind it, and what engineers, technologists, and bio-designers can learn from them.

Contents

The author described a group of marine invertebrates in each chapter and wove their unique abilities into a story that was riveting to follow. In addition to a preface and an epilogue, the following chapters were included and will be discussed in this book review.

- The Sponge’s Pharmacopoeia

- The Coral’s Castle

- The Sea Fan’s Ancient Defences

- The Sea Slug’s Sting

- The Giant Clam’s Light Trick

- The Octopus’s Shape Shift

- The Jellyfish’s Light Show

- The Sea Star’s Sticky Skin

The Sponge’s Pharmacopoeia

Sponges are ancient organisms—evidence from Nature and TheScientist suggests they may have existed 890 million years ago, nearly 20 % of Earth’s age. By comparison, modern humans have been around for only about 300,000 years, roughly 0.01 % of Earth’s history. Over this immense timespan, sponges evolved unique abilities: a sophisticated water-circulation system and the capacity to synthesize defensive chemicals. The former has inspired microfluidic applications, while the latter has fueled discoveries in immunology and biochemistry. Sponges also exhibit striking structural diversity, from massive barrel forms to elegant upright columns and dense encrusting types reinforced with spicules.

Masters of Flow

As a longtime saltwater aquarist, I knew sponges were efficient filter feeders but hadn’t appreciated how closely their flow systems mirror our own circulatory networks. Though lacking organs, sponges rely on flagellated cells (choanocytes) arranged along water channels. Water enters through multiple ostia and exits via one or more oscula. Coordinated beating of the flagella drives high-speed currents toward slower channels for feeding, gas exchange, and waste removal. These slower zones arise from increased cross-sectional area, much like capillaries in the human circulatory system, where reduced flow allows for efficient exchange.

Microbial Pharmacies

Sponges also host complex microbial communities through endosymbiosis—similar to nitrogen-fixing bacteria in plant roots or gut microbes in mammals. These symbionts aid in nutrition, defense, and skeletal formation. John Faulkner’s group at Scripps first showed that sponge-associated bacteria can produce bioactive compounds. Early proto-sponges selectively hosted beneficial cyanobacteria, which evolved to synthesize antibiotics, antifungals, anticancer agents, and even flame-retardant molecules. This chemical arsenal represents a primitive immune strategy and may explain the bright coloration of many sponges—a visual warning to predators linking color with toxicity.

The Coral’s Castle

Coral reefs are my favorite biome on Earth. They support a quarter of all marine animal species and sustain human communities through fisheries, tourism, and coastal protection. Corals are ancient animals, with fossils dating back 480–540 million years, and they’ve evolved remarkable adaptations over that time. Two standouts are their partnership with photosynthetic algae to harness sunlight and their ability to build strong skeletons through calcification. These traits have inspired innovations in materials science, sustainable energy, and additive manufacturing. Unfortunately, rising ocean temperatures are driving mass bleaching events. The very symbiosis that once gave corals an advantage now leaves sensitive species, like acroporids, vulnerable as their algae partners abandon them.

Photosynthetic Partnerships

Corals are part of the animal group Cnidarians which include sea anemones and jellyfish. Each individual coral polyp within a colony is an individual animal. The polyps form partnerships with golden-brown photosynthetic algae, or dinoflagellates, called zooxanthellae, which use pigment molecules, including chlorophyll, to produce sugars that fuel the coral’s energy needs and support calcification. Like sponges, not all corals are born with their symbionts; some must recruit them from the surrounding water. This ability likely evolved as an adaptation to the low-nutrient, shallow waters where early corals lived.

Underwater Architects

Coral polyps use energy from both photosynthesis and heterotrophy to precipitate calcium carbonate from seawater, building incredibly strong, rock-like skeletons and growing into massive colonies. Charles Darwin famously described a coral reef as “the accumulated labor of myriads of architects at work.” In fact, studies of Caribbean corals show their fracture strength ranges from 1,740 to 12,000 psi—exceeding materials like concrete and synthetic limestone.

The way corals build these skeletons is fascinating. Seawater contains negatively charged carbonate ions and positively charged calcium ions, which don’t readily bond unless the pH is high. Coral polyps pump hydrogen ions out of a specialized “working space,” raising its pH and allowing calcium and carbonate ions to form aragonite crystals—a pure form of calcium carbonate—layered intricately onto the growing skeleton.

Sunlight accelerates this process: it fuels photosynthesis in zooxanthellae, which absorb acidic CO₂ and further raise the pH, enhancing calcification. Zooxanthellae therefore play a dual role—providing energy and speeding up skeleton formation. Remarkably, coral skeletons also act like halls of mirrors, reflecting light to boost the algae’s energy production, with promising applications in fiber optics.

The Sea Fan’s Ancient Defences

Reef-building corals may seem peaceful by day, but at night they extend long tentacles armed with nematocysts to sting their neighbors in battles for space—a process the author likens to immune system defenses. Gorgonians, or sea fans, are close relatives that lack hard skeletons and sometimes zooxanthellae, and like sponges, they produce potent bioactive compounds. The chapter described a study on widespread gorgonian die-offs in the Caribbean, uncovering surprising details about their immune systems, the actual cause of mortality, and its implications for human health.

Innate Immunity

The author traveled to the Caribbean to investigate mass gorgonian die-offs and discovered that some colonies were able to fight off the disease using their immune systems. The culprit was Aspergillus sydowii, a terrestrial fungus that also infects the lungs of immunocompromised humans. In lab cultures, some corals halted the fungus’s spread, forming bright purple halos. This response was driven by amoebocytes, which deposited black granules of melanin to wall off the fungus. Chemical assays showed that these cells produced prophenoloxidase, an enzyme that triggers a cascade involving antimicrobial peptides and melanin production. This immune pathway is shared with fruit flies and other invertebrates, suggesting a common evolutionary origin and possible inheritance by vertebrates as the basis of innate immunity. Unlike adaptive immunity, which is slower but long-lasting, innate immunity is rapid and nonspecific. Vertebrates have both adaptive and innate immunity while invertebrates just have innate immunity. During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, some researchers proposed using older vaccines like BCG to stimulate innate responses early, but this approach wasn’t pursued; instead, record-time adaptive vaccines proved successful.

The Sea Slug’s Sting

Sea slugs are marine mollusks that resemble terrestrial slugs, and among them, nudibranchs stand out for their bright colors. A subgroup called aeolids feeds exclusively on cnidarians, which defend themselves with nematocysts—microscopic, harpoon-like stingers connected to venom sacs that can fire in less than a millisecond. Nudibranchs use chemo-sensory antennae called rhinophores to track their prey, then seize and consume them. The author also describes flamingo tongue cowries, predatory snails that feed on gorgonians, moving between colonies without fully consuming any single one. Remarkably, both predators not only tolerate their prey’s toxins but repurpose them: aeolid nudibranchs steal immature nematocysts for their own defense, while cowries sequester gorgonian toxins for chemical protection.

Chemical Recycling

The author describes a NOAA-funded project tracking flamingo tongue cowries feeding on gorgonians. Over the course of a week, he observed the snails moving between different gorgonian species despite the energy costs and increased predation risk. Gorgonians produce defensive toxins containing bromine and chlorine, which the cowries store and repurpose for their own chemical defense. This strategy parallels that of monarch caterpillars, which consume toxic milkweed and sequester cardiac glycosides—heart poisons that deter birds. The toxic dilution hypothesis offers an explanation for why these animals consume a variety of chemically distinct prey: by spreading intake across multiple sources, they may avoid surpassing toxicity thresholds or triggering harmful synergistic effects. This finely tuned ability to recognize and manage chemical mixtures is both ecologically fascinating and promising for applications in chemical ecology and bioengineering.

Kleptocnidae

T. Strethill Wright was the first to propose—and later confirm—that the tufted hairs on the backs of nudibranchs are actually stolen nematocysts from their cnidarian prey, a discovery later expanded by George Grosvenor. Since nematocysts fire with hair-trigger speed, the question was how they could be transported through the nudibranch’s body without discharging. Dr. Otto Glaser explored this in detail, identifying specialized cells called cnidophages, which package and transport immature nematocysts that are less likely to fire prematurely.

Modern studies on Berghia stephanieae have shown that cnidophages take up immature nematocysts through the digestive tract, transport them to cnidosacs, and ultimately deposit them in the cerata. Selection for the most potent nematocysts likely occurs in the cnidosac, though the exact mechanism remains unknown. This process, known as kleptocnidae, breaks two biological “rules”: first, nudibranchs provide a developmental environment for foreign nematocysts, regulating pH in cnidosac cells to speed their maturation; and second, they somehow avoid immune rejection of these foreign cells—possibly through immune suppression or molecular mimicry. Kleptocnidae has intriguing implications for xenotransplantation, offering insights into how foreign cells or even organs—such as pig organs for human use—might one day be integrated without immune rejection.

The Giant Clam’s Light Trick

The author recounts her first encounter with giant clams while visiting a remote peninsula in the Philippines, where nutrient-rich runoff from fish farms was clouding the water. There, he came across a 5.8-hectare giant clam nursery where researchers were restocking reefs with clams ranging from a few inches to over four feet across. Tridacna gigas, the largest species, can weigh over 500 lbs and live for a century. These clams filter phytoplankton through their massive gills, drawing water in via an incurrent siphon and expelling it through an excurrent siphon.

Their iridescent patterns come from specialized light-bending cells called iridocytes, and they also have eyespots along the mantle edge that detect shadows and movement. Giant clams form their own taxonomic family of 12 species and are close relatives of smaller, sediment-dwelling clams. They are hermaphroditic and spawn during new or full moons, releasing eggs and sperm into the water to produce planktonic larvae. Within a week, the larvae develop sensory abilities and use chemical cues to find settlement sites, possibly guided by reef sounds or signals. Once settled, they metamorphose into juveniles, hosting zooxanthellae for energy while their iridocytes bend light to optimize photosynthesis—an adaptation unique among reef invertebrates.

Light Benders

Tridacna gigas has been widely studied for its remarkable light-harvesting abilities. As it grows, the clam increasingly relies on photosynthesis, eventually meeting 100% of its energy needs through its symbiotic algae. Unlike corals, which use skeletal mirrors to amplify light, giant clams enhance this process through iridocytes—specialized cells that bend and shift light wavelengths. Algal cells are arranged in vertical columns within thin tubules that extend from the clam’s stomach, supporting the author’s hypothesis that foreign bodies—whether algae in clams and corals or nematocysts in nudibranchs—are integrated through gut outpocketing, a part of the body that naturally tolerates foreign material.

Iridocytes work by alternating layers of high refractive index guanine crystals and low refractive index cytoplasm, slowing and redirecting light. As KAUST researcher Ram Chandra Subedi explains, “guanine palettes not only reflect harmful UV radiation but also absorb it and emit light at longer, photosynthetically useful wavelengths.” Similar guanine structures appear in lizards’ reflective skin and glass frogs’ transparent blood. Yale’s Dr. Allison Sweeney notes that this design could inspire cooler, more efficient solar cells, calling giant clams “the most efficient solar energy system on Earth.”

Although they’re vulnerable to bleaching when symbionts are lost in warming seas, giant clams are relatively easy to aquaculture. By day four, larvae ingest algae, which are transported through gut tubules into skin columns. Their light-bending abilities offer exciting possibilities for energy harvesting, organic optical materials, and bio-inspired engineering.

The Octopus’s Shape Shift

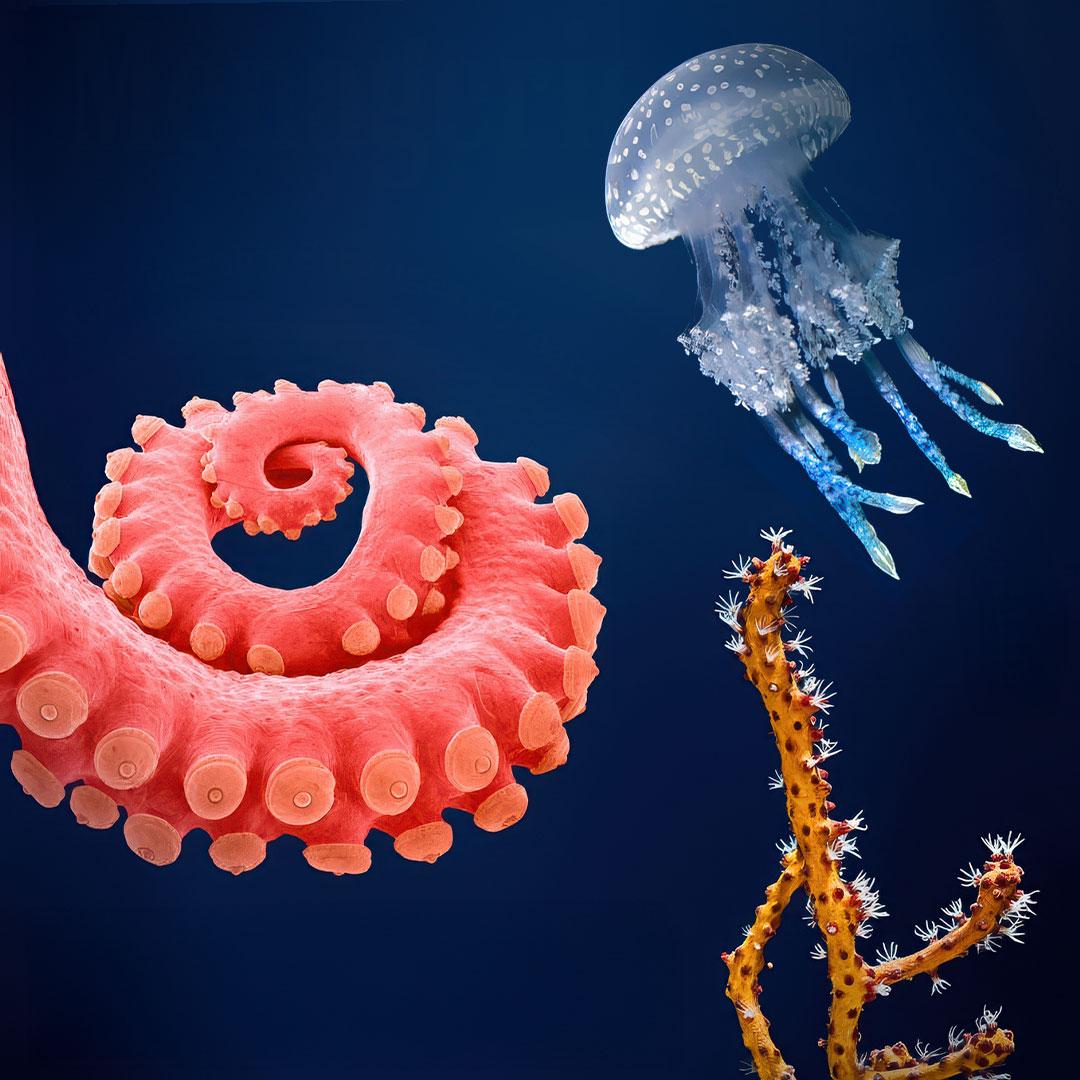

While in the Philippines for the giant clam study, the author encountered a remarkable scene on the same algae-filled reef. What he first thought was an octopus instantly changed color, texture, and behavior to mimic a drifting clump of algae, disappearing into the background within seconds. This rapid transformation—known as neural polyphenism—happens in just 200–700 milliseconds. In that moment, the octopus detected a potential threat, accessed an internal “blueprint” for algal mimicry, and reshaped itself accordingly.

Octopuses are cephalopods, molluscan relatives of clams and sea slugs, and share this rapid camouflage ability with squids and cuttlefish. Cephalopods have existed for about 545 million years, with early forms like plectronocerids predating predatory fish by 200 million years. Unlike squids, which have eight arms and two long tentacles, octopuses have eight arms, three hearts, and nine brains—one central brain and a cluster of ganglia in each arm, plus a large optic lobe. With over 300 known species, octopuses remain one of the most diverse and enigmatic animal groups, and while much has been learned about their camouflage abilities, many mechanisms behind their rapid shape-shifting are still unknown.

Masters of Disguise

Other invertebrates have color-changing chromatophores, but those of octopuses are far more complex. Each chromatophore is a tiny pigment sac surrounded by 10–30 radial muscles controlled by neurons. When activated, these muscles contract, expanding the sac and revealing red, yellow, or brown pigments (in most species). The octopus brain coordinates thousands of these cells simultaneously through a dedicated chromatophore control lobe containing over half a million neurons.

Some species take this to extremes. The blue-ringed octopus flashes iridescent blue rings produced by iridophores—cells with layered crystals similar to those in giant clam iridocytes. When threatened, its skin turns bright yellow while the rings rapidly expand, creating a striking warning display. Leucophores provide the solid background color. Octopuses also change texture using skin pouches that form jagged 3D papillae; radial and internal muscles push and shape these cones, often tipped with white. Both octopuses and cuttlefish use this trick, with studies on cuttlefish suggesting they rely on “visual assessment shortcuts”—fast visual cues that trigger pre-packaged skin patterns in as little as 125 milliseconds. Their mimicry extends beyond skin: some species alter posture and behavior to match their surroundings as well. For example, the Atlantic longarm octopus mimics the swimming style of flounders, while mimic octopuses can impersonate a range of animals, including lionfish, crabs, and sea snakes. This ability to rapidly transform color, texture, and behavior is a biological superpower inspiring new technologies. Researchers at the University of Bristol have created artificial materials that mimic chromatophore color change, while James Pikul and colleagues replicated shape-shifting skin using layered silicone and fiber meshes that inflate into 3D forms. One fascinating open question is how octopuses store and access visual blueprints—decoding complex behaviors and compressing them into rapid, deployable mimicry patterns.

The Jellyfish’s Light Show

The author opens this chapter with a blackwater dive off the coast of Hawaii—a nighttime descent into water thousands of feet deep. The goal was to observe pelagic planktonic jellies and the larval forms of squid and octopuses, which rise toward the surface at night to feed on phytoplankton and avoid daytime predators.

Cnidarian jellies are divided into three major classes—each more distinct from the others than a spider is from a butterfly. Though distantly related to corals, they diverged over 500 million years ago. The oldest group, the hydrozoans, still retain coral-like life stages, and within them, the siphonophores—such as the Portuguese man of war—display extraordinary complexity and can deliver neurotoxic stings powerful enough to kill a human. The term jellyfish broadly describes transparent, planktonic drifters, many of which belong to Cnidaria and possess stinging nematocysts. However, ctenophores (comb jellies) are look-alike relatives that lack stingers, capturing prey instead with sticky, thread-bearing cells. Recent genomic studies suggest ctenophores may represent the earliest branch of the animal kingdom, predating even sponges, since they share fewer genetic similarities with all other animals and possess a unique nerve net without synapses.

Jellies, along with many other invertebrates, are also masters of bioluminescence. In the deep and dim oceans—dark half the day even near the surface, and permanently so in the abyss—light becomes communication. It’s estimated that over 70% of marine invertebrates produce bioluminescence, using it to deter predators, attract mates, or lure prey, as seen in lanternfish and countless glowing species of the open sea.

Molecules that Glow

In nearly all light-producing organisms, bioluminescence depends on three key ingredients: oxygen, a light-emitting pigment called luciferin, and an enzyme called luciferase. When luciferin reacts with oxygen—catalyzed by luciferase—it forms an unstable, excited compound that releases light as it returns to its ground state. This reaction is often triggered by tiny amounts of calcium, which act as a molecular switch. In cnidarian jellies such as siphonophores, either cnidarian luciferase or a photoprotein like green fluorescent protein (GFP) binds with the luciferin coelenterazine. The mixture must then react with oxygen, but light isn’t produced until a cofactor—often calcium—enters the cell, precisely controlling when and how brightly the flash occurs.

Both luciferase and GFP have become invaluable fluorescent biomarkers in modern biomedical research. Their discovery traces back to Osamu Shimomura, who survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki as a teenager and later dedicated his career to understanding bioluminescence. While studying crystal jellies in the U.S., Shimomura once discarded a non-luminescent extract into a sink filled with seawater—only to see it flash blue. The missing ingredients, it turned out, were seawater’s pH and calcium ions, which catalyzed the reaction. After a year of meticulous work, he isolated the responsible protein, aequorin.

Shimomura discovered that aequorin produces blue light when calcium binds to it and that it contains the luciferin coelenterazine, which jellies cannot synthesize themselves but instead acquire from crustacean prey. He also found that crystal jellies emit green light via a separate pathway involving green fluorescent protein (GFP). Shimomura later purified and crystallized GFP, while Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien cloned the gene and demonstrated its use as a fluorescent marker. Their work earned all three scientists the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Aequorin’s light is calcium-sensitive, flashing with remarkable precision—making it a powerful tool for studying calcium signaling in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. GFP, meanwhile, has revolutionized biology, allowing scientists to tag and visualize cells, tissues, and processes—from developing neurons to immune responses, to even tracing nematocyst pathways in nudibranchs. Today, these glowing proteins illuminate the living world in ways once only imagined beneath the ocean’s surface.

The Sea Star’s Sticky Skin

Sea stars roam intertidal rocky shores in search of slow-moving prey like clams, oysters, and mussels. They move on five arms lined with thousands of tube feet, each powered by a water-based hydraulic system that channels fluid through canals and valves, with muscles controlling pressure in each tiny foot. They have no true brain—only simple eyespots at the tips of their arms and a mouth on their underside. Most of the 2,000+ sea star species have five arms, though some have more in multiples of five, and rare species have six or eight. Each arm houses digestive glands and gonads. Because they cannot regulate internal salt levels, they live only in seawater, not freshwater or on land. Like octopuses, they can also change the texture of their skin under neural control.

Sea stars belong to the echinoderms—“spiny-skinned” animals that also include sea urchins, brittle stars, and sea cucumbers. This group originated around 540 million years ago and is more closely related to humans than to mollusks, cnidarians, or sponges.

In this chapter, the author visits the rocky shores of Tatoosh Island in the Pacific Northwest, where ecologist Bob Paine studied the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus), a bright purple or orange species. Paine discovered that it functions as a keystone species—a few individuals can shape entire ecosystems. When ochre stars were present, mussel populations stayed in check, allowing a more diverse community to flourish, including brown, green, and red algae, pink coralline algae, green anemones, red sea squirts, and purple sea urchins.

In the next sections, I’ll focus on two remarkable abilities of sea stars: their tug-of-war feeding strategy to pry open mussels, and their neural control of skin texture—both of which have fascinating real-world applications.

Hydraulic Hunters

How do sea stars pry open tightly shut clams, oysters, and mussels held closed by powerful adductor muscles? They use patience and strength. A sea star grips each shell half with its tube feet and applies a steady pulling force—often more than 1.8 pounds—for hours, sometimes up to half a day. Eventually, the bivalve’s muscles fatigue, and even the smallest gap—just 0.1 millimeters—is enough. At that moment, the sea star everts its stomach into the shell and begins digesting the animal from the inside.

What makes this possible is the unique biology of sea star skin—a tissue capable of shifting between soft and rigid states, giving them both endurance and strength. This remarkable material is the secret behind their slow-motion victory.

Programmable Stiffness

Sea star skin can switch from soft to rigid in seconds and stay that way for hours—with almost no energy cost. This ability comes from a special material in their body called mutable collagenous tissue (MCT). Their skin contains spines and a framework of calcareous struts surrounded by collagen fibers. When triggered by nerves—not muscles—the collagen fibrils instantly cross-link, locking the struts together like the teeth of a zipper. The result is a stiff, armor-like structure anchored to an internal skeleton of calcified spicules.

This neural control of stiffness is unique among invertebrates. It lets sea stars hold a powerful prying posture for hours while opening prey like mussels, without exhausting energy. Because this stiffness is triggered electrically via nerves rather than mechanically via muscles, the response is both fast and energy-efficient.

MCT has exciting applications in smart materials and bioengineering. In 2000, John Trotter and colleagues engineered a hybrid material using sea cucumber collagen fibers embedded in a synthetic matrix. Light or electricity could turn cross-links on or off, changing the stiffness of the material. Since human tissues like skin, tendon, and bone are also made of collagen, marine-derived MCT is being explored for reconstructive surgery and adaptive biomaterials.

Conclusion

The Ocean’s Menagerie is a tour of living technologies—pumps, solar panels, stingers, light switches, smart skins—evolved underwater over millions of years. Harvell makes the biology legible and the engineering implications obvious: there’s a playbook here for materials science, optics, robotics, and medicine. Her epilogue also lands a necessary punchline: climate change is already reshaping the oceans, and many of these invertebrate “technologies” are failing under heat, acidification, and disease. If we want to keep borrowing from nature’s R&D lab, we have to help keep that lab alive. For me, that’s the takeaway—learn from these organisms, build with their principles, and invest in the conservation that makes future bio-inspired breakthroughs possible.